Wendy Campbell-Purdie: plant hunter

Posted:8 March 2015

At our highly enjoyable Reading Evening back on 27 February local author Pat Bowen talked in particular about two women ‘plant hunters’, Wendy Campbell-Purdie and Marianne North. Here Pat has written about Campbell-Purdie – very appropriate we thought for International Women’s Day, it makes fascinating reading:

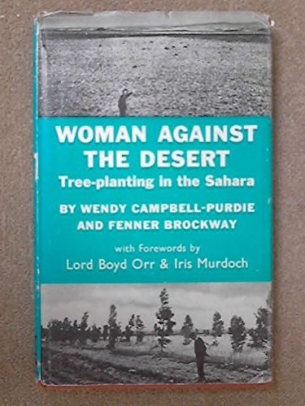

Wendy Campbell-Purdie, who was born to a farming family in New Zealand, lived in Oxford in the UK in the 1950s. Iris Murdoch, with whom she was friends at that time wrote an introduction for Wendy’s only book: “Woman against the Desert”* There is little personal history in this short book. It focuses on Wendy’s conviction that a Green Front of trees would be a way of preventing the inexorable advance of the Sahara, and her own work in proving it.

Wendy Campbell-Purdie, who was born to a farming family in New Zealand, lived in Oxford in the UK in the 1950s. Iris Murdoch, with whom she was friends at that time wrote an introduction for Wendy’s only book: “Woman against the Desert”* There is little personal history in this short book. It focuses on Wendy’s conviction that a Green Front of trees would be a way of preventing the inexorable advance of the Sahara, and her own work in proving it.

Her love of trees began in Corsica where she worked for a logging company – a move she may have made after a relationship breakdown in England. She improved her French during this period, learned much about timber and observed the effects of felling too many trees. She began what remained a life-long practice: reading and learning everything she could about all aspects of arboriculture though she never obtained an academic qualification in it.

She returned to England with an idea about importing Corsican pines to the UK. With this plan, she met Richard St Barbe Baker who’d already founded ‘Men of the Trees’ and begun working on the idea of using trees to change the micro-climates of arid lands and make them fertile. Wendy took on his ideas, realising from her own experience the value of trees for making topsoil, stabilising ground-water and creating more likelihood of rain as well as providing food and shelter.

In the early 1960s she set off for Morocco (with a one-way ticket – she couldn’t afford a return) and rented a small plot of land near Tiznit. She met government officials and tried to interest them in her project but she was fobbed off. She began raising her seedling trees, and planting: eventually 2000 trees. She tried various kinds, some of which flourished and some didn’t. She also experimented with different grasses and grains. She had an 80% success rate with the trees and, within 4 years, some were 12’ high and there was grain growing in their shelter.

Wendy had proved it could be done, but the political situation in Morocco was becoming intolerably oppressive. While living there, she met and warmed to refugees from Algeria, which was in the midst of its war of independence from France. She resolved to go to Algeria as soon as it was possible and continue her work there.

During the 1960s she regularly travelled to Australia and the UK to talk about the work in Tiznit, and to raise funds. She had very limited financial means and had to take jobs in journalism and translating to make ends meet.

As soon as the situation in Algeria settled, she went to Bou Saada, and was given land by the new government: a dump site left by the French army. She had money from War on Want at this point and she also set up a Trust to fund the tree planting. Her work was becoming more widely known, and volunteers arrived from many countries to begin the planting. In the first winter, it was 65,000 seedlings: olives, citrus, figs, cypress, acacia and various eucalypts. Again, she achieved an 80% survival rate despite flash floods, locusts and other vicissitudes.

It’s hard to find biographical information about Wendy Campbell-Purdie, but online there’s a report from the Sydney Herald of 1972 describing how fruit, vegetables and grain are growing well in the shelter belt created by the trees at Bou Saada.

It’s hard to find biographical information about Wendy Campbell-Purdie, but online there’s a report from the Sydney Herald of 1972 describing how fruit, vegetables and grain are growing well in the shelter belt created by the trees at Bou Saada.

Wendy’s 130,000 trees are a very small number in relation to the whole Sahara, but since her time, various North African governments have taken up the idea. She was a pioneer, and as is the nature of pioneering, she apparently made some mistakes in her planting choices. Such mistakes provide very useful information for those who follow pioneers. She was not mistaken however, in her beliefs, which she proved valid in the most practical of ways – on the ground. Her work was rooted in awareness of the value of trees and associated biodiversity in halting the spread of the desert, providing food (directly and indirectly) for people and livestock, and creating a micro climate that made rain more likely. As she worked in Morocco and Algeria, she also became more and more aware of the value of tree planting and nurturing in offering good employment in areas where unemployment rates were well over 50%.

Wendy Campbell-Purdie showed what is possible.